Building your own transliterations

Nominatim transliterates all scripts to Latin to make sure that search works across different scripts. The standard transliteration does not work for all languages equally well. This tutorial shows how to add custom transliterations for selected areas of the world using the example of Cantonese in Hongkong.

This tutorial assumes that you have read about the ICU tokenizer and have some experience with programming in Python.

The transliteration problem

Transliteration is the conversion from one script to another. It is an important topic in geocoding because it enables users of one script to search for places in areas where a different script is used. When you type a query into the search box, this query is usually transliterated into Latin script. The same has happened with the place names when they were imported from OpenStreetMap data. They are not saved in their original script in the search index but are first transliterated to Latin. As a result, it does not matter in what script the place name was in or how the query was typed. As long as the transliteration matches, it will be found.

Problems start when there is more than one obvious transliteration for a script. A famous example where the approach fails is Chinese script. It is used by Mandarin speakers as well as Cantonese speakers. The two groups have very different ways of pronouncing the characters of the script and therefore also very different transliterations. Nominatim uses the ICU library for creating the transliteration of Chinese script. ICU in turn uses the Pinyin system, the standard romanization system for Mandarin. The pronunciation of Cantonese names is very different from that.

We cannot simply assign different methods of transliteration for Cantonese and Mandarin names. When a user types a query, we don’t know in advance if they are looking for a name in Cantonese or Mandarin. However, what we can do is to add an additional transliteration to Cantonese names. This means they will show up in the search index with the standard Pinyin transliteration and the correct Cantonese transliteration. The user then can find the names in both Chinese script and the Cantonese romanization of the name.

This tutorial shows how to write your own custom token analysers that work for a very specific part of the world and add an additional transliteration variant.

Note: much of the code in this tutorial was inspired by Sven Geggus’ transliteration service for the German OpenStreetMap map style. Have a look at the project if you are interested in other transliterations that he has used.

Writing your own token analysis

When you want to add an additional variation to a place name to the search index, then the token analysis module is the right place to start. It takes a name from OSM and creates all the tokens that are eventually added to the search index. The generic token analysis has some powerful mechanisms to create spelling variants for a single name. But it is not well suited for a logographic script with thousands of symbols. Instead we are going to use the pinyin-jyutping-sentence library, which does all the heavy lifting for us.

Setting up the custom module

Adding a custom tokenizer analysis to your installation is as simple as putting

a Python file into your project directory that implements the appropriate

interface. Lets start with the minimal boilerplate for a token analysis. Put

the following file as cantonese_analysis.py into your project directory:

class CantoneseAnalysis:

def __init__(self, norm, trans):

self.norm = norm

self.trans = trans

def get_canonical_id(self, name):

return self.norm.transliterate(name.name).strip()

def compute_variants(self, canonical_id):

return [self.trans.transliterate(canonical_id)]

def configure(rules, normalizer, transliterator):

return None

def create(normalizer, transliterator, config):

return CantoneseAnalysis(normalizer, transliterator)

configure() and create() are the two functions called by Nominatim to set

up the token analyzer. The CantoneseAnalysis class implements the actual

analyzer. At the moment, our analyzer does the minimum that the name can be

found as is: it needs to run the global norm transliteration and the

global trans transliteration on the input name. The search frontend will

later do exactly the same with the incoming query. So to make sure that

search entry and query can match, never forget to apply these two transliterators.

To use your custom token analysis, you need to customize the configuration of

the ICU tokenizer. Copy the default configuration from

settings/icu_tokenizer.yaml into your project directory. Make sure it keeps

the name icu_tokenizer.yaml. There are already a lot of language-specific

token analysis modules set up. Add your custom module for the zh language

in the appropriate section:

...

token-analysis:

- analyzer: generic

- id: zh

analyzer: cantonese_analysis.py

...

If the analyzer is the name of a Python file, then Nominatim will try to find the file relative to the project directory.

You also need the ‘zh’ language to the whitelist of languages that are tagged by the tag-analyzer-by-language sanitizer:

- step: tag-analyzer-by-language

filter-kind: [".*name.*"]

whitelist: [bg,ca,cs,da,de,el,en,es,et,eu,fi,fr,gl,hu,it,ja,mg,ms,nl,no,pl,pt,ro,ru,sk,sl,sv,tr,uk,vi,zh]

use-defaults: all

mode: append

This makes sure that your analyzer zh is called for all names with a

:zh suffix. These are names in Chinese script as per OSM tagging convention.

You can run the new configuration against a small import now. It should run successfully through but change nothing because right now our analysis does the same as the generic analysis when run without configuration.

Adding additional transliteration variants

Now it is time to add the jyutping transliteration library. First install the library via pip:

pip install pinyin-jyutping-sentence

We need only one function from the library: jyutping() which transliterates

names using the Cantonese romanization we want. Adding an additional variant in the

compute_variants function is simple. Change the function in

your cantonese_analysis.py module like this:

from pinyin_jyutping_sentence import jyutping

...

def compute_variants(self, canonical_id):

variants = [self.trans.transliterate(canonical_id)]

latin = self.trans.transliterate(jyutping(canonical_id))

if latin:

variants.append(latin)

return variants

The first line adds the usual transliteration to the list of variants. This is

important to do or you won’t be able to find the places in Chinese script

anymore. Next we compute the Jyutping transliteration. The function returns

a romanized string but not necessarily a string that is compatible with the

transliteration used by the query frontend. For example, Jyutping adds accents

to mark the tones. Nominatim’s default transliteration does not have any accents.

That is why the result is transliterated again with

the trans transliterator. You should always do this to be on the save side.

Sometimes you may even have to run your transformation results through the

norm transliterator again, too. This is for example the case when your

transformation results in upper case letters. These are already removed during

normalization in the default configuration. Have a look at the ICU rules for

normalization in your icu_tokenizer.yaml to understand which transformations

are done when.

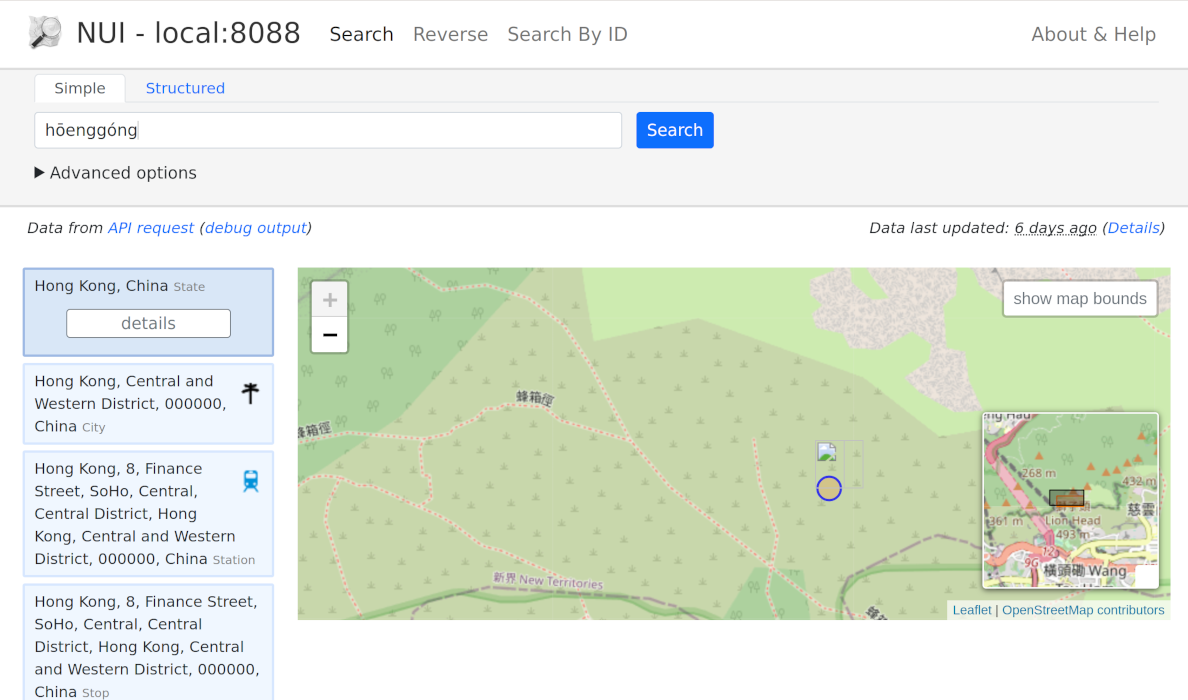

These are all the changes needed to add the custom transliteration. Let’s try this out. The Jyutping transliteration for Hongkong(香港) is ‘Hōenggóng’. Searching on nominatim.openstreetmap.org yields no results. If we import an extract of Hongkong with the custom token analysis, the search works well:

Searching for ‘香港’ works too, of course.

Writing your own sanitizer

The token analysis adds Jyutping transliteration but it has a minor flaw. It adds the transliteration to all names in Chinese script including those in areas where Mandarin is spoken. It doesn’t hurt but it adds unnecessary variants which increase the database size and may lead to false positives in the results. Therefore, in a second step, we want to restrict the use of our new token analysis to places in Hongkong. This is the task of a sanitizer. It goes through the names of the input data and transforms them before they are prepared by the token analysis. The sanitizer also decides which token analysis module will be used for each name. This is what we need.

Setting up a custom sanitizer

Like above, lets start with setting up a simple custom sanitizer that does nothing. This is done exactly in the same way as with the token analysis: add a Python file with the sanitizer implementation to your project directory. Here is the basic outline of a sanitizer module:

def create(config):

def _run(obj):

pass

return _run

The core of a sanitizer is a function that processes a place information and

manipulates names and address names in place. The function again needs to be

returned through a create() function exported by the module.

Save the code as tag_cantonese.pyin your project directory. Now you can add

it to the list of sanitizers in your icu_tokenizer.yaml:

...

sanitizers:

...

- step: tag_cantonese.py

...

Make sure to add your sanitizer to the end of the list. Sanitizers are executed in the order that they been put in the list. In our case we would like to benefit from the processing of the other sanitizers, for example, from the one that splits list of names into single items.

That is all, your sanitizer will now be used for the next import.

Using a sanitizer to filter by area

The sanitizer function receives an object with three fields:

placecontains read-only information about the place being processednamescontains a editable list of namesaddresscontains a editable list of address fields connected to the place

The place information has already information in which country the place is located. This is however not much use in the case of Hongkong as this is part of China. To find places in Hongkong, we have instead of compare the centroid location of the place with the area of Hongkong.

We use the shapely library for the geometry operations. If you are on Ubuntu/Debian, you can install it through apt:

sudo apt-get install python3-shapely

Otherwise, you can install shapely via pip:

pip install shapely

The osml10n project already has a simplified geojson of Hongkong, which we can use for our purpose. Go to the project directory, then download the file:

wget -O hk.geojson https://raw.githubusercontent.com/giggls/osml10n/master/boundaries/hk.geojson

Now the sanitizer needs to load the geojson into a shapely geometry. We use prepared geometries here, because they are much faster to use later. Add the following code to your custom sanitizer:

import json

from pathlib import Path

from shapely.geometry import Point, shape

import shapely.prepared

# Look for the geojson file in the same directory where this source file is.

HK_GEOJSON_LOCATION = (Path(__file__) / '..' / 'hk.geojson').resolve()

def get_geometry():

with HK_GEOJSON_LOCATION.open('r') as fd:

geojson = json.load(fd)['features'][0]['geometry']

return shapely.prepared.prep(shape(geojson))

Now all the parts are in place to implement the actual sanitizer function.

Change the create() function as follows:

def create(config):

hongkong_geometry = get_geometry()

def tag_cantonese(obj):

if obj.names:

centroid = obj.place.centroid

if centroid is not None and hongkong_geometry.contains(Point(*centroid)):

for name in obj.names:

if name.suffix == 'zh':

name.set_attr('analyzer', 'cantonese')

return tag_cantonese

When the create function is called, it first creates a fresh shapely geometry for us. The sanitizer function itself first checks if the object has any names at all and then if the place is inside our Hongkong polygon. Then it goes through all the names and where it finds one that is in Chinese script (the ones with name suffix ‘zh’) then it sets the ‘analyzer’ attribute so that our custom analyzer is used.

Where to go from here

The examples in this tutorial are just meant to give you a first introduction into sanitizers and token analysis. They can be used for many more pre-processing tasks. Have a look at the modules that ship with Nominatim to get an idea about what can be done.

One thing to keep in mind when developing your custom code is performance. Sanitizer and token analysis functions are called for every single place to be processed that’s nore than 200 million times for a planet import. Making sure that your custom modules are efficient can easily make difference of a day for so much data.